Id Painting/lonely Old Woman in Front of Stove Reading

| Edward Hopper | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | (1882-07-22)July 22, 1882 Nyack, New York, U.S. |

| Died | May 15, 1967(1967-05-15) (anile 84) Manhattan, New York, U.South. |

| Known for | Painting |

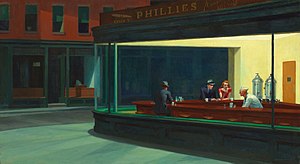

| Notable piece of work | Automat (1927) Chop Suey (1929) Nighthawks (1942) Office in a Pocket-size Urban center (1953) |

| Spouse(s) | Josephine Nivison (1000. 1924) |

Edward Hopper (July 22, 1882 – May 15, 1967) was an American realist painter and printmaker. While he is widely known for his oil paintings, he was equally proficient every bit a watercolorist and printmaker in carving. His career benefited decisively from his union to swain-creative person Josephine Nivison, who contributed much to his work, both every bit a life-model and as a creative partner. Hopper was a minor-key artist, creating subdued drama out of commonplace subjects 'layered with a poetic meaning', inviting narrative interpretations, oft unintended. He was praised for 'consummate verity' in the America he portrayed.

Biography [edit]

Early on life [edit]

Childhood abode of Edward Hopper in Nyack, New York

Hopper was born in 1882 in Nyack, New York, a yacht-building center on the Hudson River due north of New York Urban center.[1] [ii] He was one of ii children of a comfortably well-off family. His parents, of mostly Dutch ancestry, were Elizabeth Griffiths Smith and Garret Henry Hopper, a dry-goods merchant.[3] Although not equally successful as his forebears, Garrett provided well for his 2 children with considerable help from his wife's inheritance. He retired at age forty-nine.[4] Edward and his only sister Marion attended both individual and public schools. They were raised in a strict Baptist home.[5] His father had a mild nature, and the household was dominated by women: Hopper's female parent, grandmother, sister, and maid.[6]

His birthplace and boyhood dwelling was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2000. It is now operated equally the Edward Hopper House Art Center.[vii] Information technology serves as a nonprofit community cultural center featuring exhibitions, workshops, lectures, performances, and special events.[8]

Vase (1893), example of Edward Hopper's earliest signed and dated artwork with attention to low-cal and shadow.

Hopper was a proficient student in grade schoolhouse and showed talent in cartoon at age v. He readily captivated his male parent's intellectual tendencies and love of French and Russian cultures. He also demonstrated his mother's artistic heritage.[nine] Hopper's parents encouraged his art and kept him handsomely supplied with materials, instructional magazines, and illustrated books. Hopper first began signing and dating his drawings at the age of ten. The earliest of these drawings include charcoal sketches of geometric shapes, including a vase, bowl, cup and boxes.[10] The detailed test of low-cal and shadow which carried on throughout the rest of his career can already be plant in these early on works.[10] By his teens, he was working in pen-and-ink, charcoal, watercolor, and oil—drawing from nature also equally making political cartoons.[11] In 1895, he created his first signed oil painting, Rowboat in Rocky Cove, which he copied from a reproduction in The Art Interchange, a popular journal for amateur artists. Hopper's other earliest oils such every bit Old ice pond at Nyack and his c.1898 painting Ships have been identified every bit copies of paintings by artists including Bruce Crane and Edward Moran.[12] [thirteen]

In his early on self-portraits, Hopper tended to represent himself as skinny, ungraceful, and homely. Though a tall and quiet teenager, his prankish sense of humor found outlet in his art, sometimes in depictions of immigrants or of women dominating men in comic situations. Later in life, he mostly depicted women equally the figures in his paintings.[14] In high school (he graduated from Nyack High School in 1899),[15] he dreamed of beingness a naval architect, merely after graduation he alleged his intention to follow an art career. Hopper's parents insisted that he study commercial art to have a reliable means of income.[16] In developing his self-paradigm and individualistic philosophy of life, Hopper was influenced past the writings of Ralph Waldo Emerson. He later said, "I admire him greatly...I read him over and over once again."[17]

Hopper began art studies with a correspondence grade in 1899. Soon he transferred to the New York School of Art and Pattern, the forerunner of Parsons The New Schoolhouse for Design. There he studied for 6 years, with teachers including William Merritt Chase, who instructed him in oil painting.[xvi] Early, Hopper modeled his way after Hunt and French Impressionist masters Édouard Manet and Edgar Degas.[eighteen] Sketching from alive models proved a claiming and a shock for the conservatively raised Hopper.

Another of his teachers, artist Robert Henri, taught life course. Henri encouraged his students to use their art to "brand a stir in the world". He also advised his students, "Information technology isn't the subject that counts but what you feel about information technology" and "Forget nigh art and paint pictures of what interests you in life."[16] In this manner, Henri influenced Hopper, as well every bit futurity artists George Bellows and Rockwell Kent. He encouraged them to imbue a modern spirit in their piece of work. Some artists in Henri's circumvolve, including John Sloan, became members of "The Viii", also known every bit the Ashcan School of American Fine art.[nineteen] Hopper'south first surviving oil painting to hint at his utilise of interiors every bit a theme was Solitary Figure in a Theater (c.1904).[xx] During his student years, he too painted dozens of nudes, still life studies, landscapes, and portraits, including his self-portraits.[21]

In 1905, Hopper landed a part-time chore with an advertising agency, where he created cover designs for merchandise magazines.[22] Hopper came to detest illustration. He was bound to it by economic necessity until the mid-1920s.[23] He temporarily escaped past making three trips to Europe, each centered in Paris, ostensibly to study the art scene at that place. In fact, still, he studied alone and seemed mostly unaffected past the new currents in art. Later he said that he "didn't think having heard of Picasso at all".[19] He was highly impressed by Rembrandt, particularly his Night Watch, which he said was "the almost wonderful thing of his I have seen; it's past belief in its reality."[24]

Hopper began painting urban and architectural scenes in a dark palette. Then he shifted to the lighter palette of the Impressionists earlier returning to the darker palette with which he was comfortable. Hopper later on said, "I got over that and later things done in Paris were more the kind of things I practice now."[25] Hopper spent much of his time drawing street and café scenes, and going to the theater and opera. Unlike many of his contemporaries who imitated the abstract cubist experiments, Hopper was attracted to realist art. Later on, he admitted to no European influences other than French engraver Charles Meryon, whose moody Paris scenes Hopper imitated.[26]

Years of struggle [edit]

After returning from his last European trip, Hopper rented a studio in New York Metropolis, where he struggled to ascertain his own style. Reluctantly, he returned to illustration to support himself. Being a freelancer, Hopper was forced to solicit for projects, and had to knock on the doors of mag and agency offices to find business.[27] His painting languished: "it's difficult for me to decide what I want to paint. I go for months without finding it sometimes. It comes slowly."[28] His fellow illustrator Walter Tittle described Hopper'southward depressed emotional state in sharper terms, seeing his friend "suffering...from long periods of unconquerable inertia, sitting for days at a fourth dimension before his easel in helpless unhappiness, unable to raise a paw to pause the spell."[29]

In 1912 (February 22 to March 5) he was included in the exhibition of The Independents a grouping of artists at the initiative of Robert Henri but did not make any sales.[28]

In 1912, Hopper traveled to Gloucester, Massachusetts, to seek some inspiration and made his first outdoor paintings in America.[28] He painted Squam Light, the first of many lighthouse paintings to come up.[thirty]

Hopper'due south prizewinning affiche, Smash the Hun (1919), reproduced on the front end encompass of the Morse Dry out Dock Dial

In 1913, at the Armory Show, Hopper earned $250 when he sold his offset painting, Sailing (1911), to an American businessman Thomas F Vietor, which he had painted over an before self-portrait.[31] Hopper was thirty-one, and although he hoped his first sale would lead to others in brusque order, his career would not catch on for many more years.[32] He connected to participate in group exhibitions at smaller venues, such as the MacDowell Club of New York.[33] Shortly subsequently his father's expiry that same yr, Hopper moved to the 3 Washington Square Due north apartment in the Greenwich Hamlet department of Manhattan, where he would live for the balance of his life.

Night on the El Railroad train (1918) past Edward Hopper

The following yr he received a commission to create some motion-picture show posters and handle publicity for a picture company.[34] Although he did not like the illustration work, Hopper was a lifelong devotee of the cinema and the theatre, both of which he treated as subjects for his paintings. Each course influenced his compositional methods.[35]

At an impasse over his oil paintings, in 1915 Hopper turned to etching. By 1923 he had produced nigh of his approximately seventy works in this medium, many of urban scenes of both Paris and New York.[36] [37] He also produced some posters for the war endeavour, as well as continuing with occasional commercial projects.[38] When he could, Hopper did some outdoor oil paintings on visits to New England, especially at the art colonies at Ogunquit, and Monhegan Island.[39]

During the early on 1920s his etchings began to receive public recognition. They expressed some of his later themes, every bit in Night on the El Train (couples in silence), Evening Air current (lone female person), and The Catboat (simple nautical scene).[twoscore] Two notable oil paintings of this fourth dimension were New York Interior (1921) and New York Eating house (1922).[41] He besides painted two of his many "window" paintings to come: Girl at Sewing Machine and Moonlight Interior, both of which bear witness a figure (clothed or nude) near a window of an apartment viewed as gazing out or from the point of view from the exterior looking in.[42]

Although these were frustrating years, Hopper gained some recognition. In 1918, Hopper was awarded the U.Due south. Shipping Board Prize for his war poster, "Smash the Hun". He participated in three exhibitions: in 1917 with the Society of Independent Artists, in January 1920 (a one-human exhibition at the Whitney Studio Order, which was the precursor to the Whitney Museum), and in 1922 (again with the Whitney Studio Order). In 1923, Hopper received two awards for his etchings: the Logan Prize from the Chicago Society of Etchers, and the W. A. Bryan Prize.[43]

Marriage and breakthrough [edit]

By 1923, Hopper'southward slow climb finally produced a breakthrough. He re-encountered Josephine Nivison, an artist and former student of Robert Henri, during a summertime painting trip in Gloucester, Massachusetts. They were opposites: she was brusque, open up, gregarious, sociable, and liberal, while he was alpine, secretive, shy, placidity, introspective, and conservative.[38] They married a year afterwards with artist Guy Pene du Bois as their best human.[3] She remarked: "Sometimes talking to Eddie is merely like dropping a rock in a well, except that it doesn't thump when it hits bottom."[44] She subordinated her career to his and shared his reclusive life style. The rest of their lives revolved around their spare walk-up flat in the city and their summers in South Truro on Cape Cod. She managed his career and his interviews, was his principal model, and was his life companion.[44]

With Nivison's help, vi of Hopper's Gloucester watercolors were admitted to an showroom at the Brooklyn Museum in 1923. 1 of them, The Mansard Roof, was purchased by the museum for its permanent collection for the sum of $100.[45] The critics mostly raved about his work; one stated, "What vitality, force and directness! Discover what can exist done with the homeliest subject field."[45] Hopper sold all his watercolors at a i-homo show the following yr and finally decided to put analogy behind him.

The artist had demonstrated his ability to transfer his allure to Parisian compages to American urban and rural architecture. According to Boston Museum of Fine Arts curator Ballad Troyen, "Hopper really liked the manner these houses, with their turrets and towers and porches and mansard roofs and ornament bandage wonderful shadows. He always said that his favorite thing was painting sunlight on the side of a house."[46]

At 40-ane, Hopper received farther recognition for his work. He continued to harbor bitterness nigh his career, later turning down appearances and awards.[44] With his financial stability secured by steady sales, Hopper would alive a elementary, stable life and go along creating art in his personal style for four more decades.

His Two on the Alley (1927) sold for a personal record $1,500, enabling Hopper to purchase an automobile, which he used to brand field trips to remote areas of New England.[47] In 1929, he produced Chop Suey and Railroad Sunset. The following twelvemonth, art patron Stephen Clark donated House by the Railroad (1925) to the Museum of Modern Art, the first oil painting that information technology acquired for its collection.[48] Hopper painted his last cocky-portrait in oil around 1930. Although Josephine posed for many of his paintings, she sat for only one formal oil portrait past her husband, Jo Painting (1936).[49]

Hopper fared amend than many other artists during the Great Low. His stature took a sharp rising in 1931 when major museums, including the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, paid thousands of dollars for his works. He sold 30 paintings that twelvemonth, including 13 watercolors.[47] The following year he participated in the first Whitney Annual, and he continued to exhibit in every annual at the museum for the balance of his life.[47] In 1933, the Museum of Modernistic Art gave Hopper his first large-scale retrospective.[50]

In 1930, the Hoppers rented a cottage in South Truro, on Cape Cod. They returned every summertime for the rest of their lives, building a summertime house there in 1934.[51] From there, they would take driving trips into other areas when Hopper needed to search for fresh cloth to paint. In the summers of 1937 and 1938, the couple spent extended sojourns on Wagon Wheels Subcontract in South Royalton, Vermont, where Hopper painted a series of watercolors forth the White River. These scenes are atypical among Hopper's mature works, as most are "pure" landscapes, devoid of architecture or homo figures. Showtime Co-operative of the White River (1938), now in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, is the best-known of Hopper'southward Vermont landscapes.[52]

Hopper was very productive through the 1930s and early 1940s, producing among many important works New York Movie (1939), Girlie Bear witness (1941), Nighthawks (1942), Hotel Foyer (1943), and Morning in a Metropolis (1944). During the late 1940s, yet, he suffered a period of relative inactivity. He admitted: "I wish I could pigment more. I become sick of reading and going to the movies."[53] During the next 2 decades, his health faltered, and he had several prostate surgeries and other medical issues.[53] Only, in the 1950s and early 1960s, he created several more major works, including First Row Orchestra (1951); every bit well as Morning Sun and Hotel by a Railroad, both in 1952; and Intermission in 1963.[54]

Death [edit]

Where Hopper lived in New York City, three Washington Square N

Gravestone Edward and Josephine H., Oak Hill Cemetery, Nyack

Hopper died of natural causes in his studio most Washington Square in New York Urban center on May xv, 1967. He was buried two days afterward in the family plot at Oak Hill Cemetery in Nyack, New York, his place of birth.[55] His wife died x months afterward and is cached with him.

His wife bequeathed their joint collection of more 3 thousand works to the Whitney Museum of American Fine art.[56] Other significant paintings by Hopper are held by the Museum of Modern Fine art in New York, The Des Moines Fine art Middle, and the Art Institute of Chicago.

Art [edit]

Personality and vision [edit]

Always reluctant to talk over himself and his art, Hopper but said, "The whole answer is there on the canvas."[50] Hopper was stoic and fatalistic—a placidity introverted human with a gentle sense of sense of humor and a frank manner. Hopper was someone drawn to an emblematic, anti-narrative symbolism,[57] who "painted brusque isolated moments of configuration, saturated with suggestion".[58] His silent spaces and uneasy encounters "touch us where nosotros are about vulnerable",[59] and have "a suggestion of melancholy, that melancholy being enacted".[threescore] His sense of color revealed him as a pure painter[61] as he "turned the Puritan into the purist, in his quiet canvasses where blemishes and blessings balance".[62] Co-ordinate to critic Lloyd Goodrich, he was "an eminently native painter, who more than any other was getting more than of the quality of America into his canvases".[63] [64]

Conservative in politics and social matters (Hopper asserted for instance that "artists' lives should be written by people very close to them"),[65] he accepted things every bit they were and displayed a lack of idealism. Cultured and sophisticated, he was well-read, and many of his paintings show figures reading.[66] He was mostly proficient company and unperturbed by silences, though sometimes taciturn, grumpy, or detached. He was e'er serious about his art and the fine art of others, and when asked would return frank opinions.[67]

Hopper's most systematic annunciation of his philosophy equally an artist was given in a handwritten note, entitled "Statement", submitted in 1953 to the periodical, Reality:

Cracking art is the outward expression of an inner life in the creative person, and this inner life will result in his personal vision of the earth. No amount of skilful invention can replace the essential chemical element of imagination. One of the weaknesses of much abstruse painting is the attempt to substitute the inventions of the man intellect for a individual imaginative formulation.

The inner life of a human being is a vast and varied realm and does not concern itself alone with stimulating arrangements of color, form and design.

The term life used in art is something not to be held in antipathy, for it implies all of beingness and the province of fine art is to react to it and non to shun information technology.

Painting will accept to bargain more fully and less obliquely with life and nature'southward phenomena before it can again become great.[68]

Though Hopper claimed that he didn't consciously embed psychological meaning in his paintings, he was deeply interested in Freud and the power of the subconscious heed. He wrote in 1939, "So much of every art is an expression of the hidden that information technology seems to me almost of all the important qualities are put there unconsciously, and little of importance past the conscious intellect."[69]

Methods [edit]

Although he is best known for his oil paintings, Hopper initially achieved recognition for his watercolors and he also produced some commercially successful etchings. Additionally, his notebooks incorporate high-quality pen and pencil sketches, which were never meant for public viewing.

Hopper paid item attention to geometrical design and the careful placement of human figures in proper balance with their environment. He was a slow and methodical artist; every bit he wrote, "It takes a long time for an idea to strike. And so I have to recall about it for a long fourth dimension. I don't outset painting until I have it all worked out in my mind. I'g all right when I get to the easel".[70] He often made preparatory sketches to piece of work out his carefully calculated compositions. He and his wife kept a detailed ledger of their works noting such items every bit "deplorable face up of woman unlit", "electric light from ceiling", and "thighs cooler".[71]

For New York Movie (1939), Hopper demonstrates his thorough preparation with more than 53 sketches of the theater interior and the figure of the pensive usherette.[72]

The effective use of light and shadow to create mood too is central to Hopper'due south methods. Brilliant sunlight (as an emblem of insight or revelation), and the shadows information technology casts, as well play symbolically powerful roles in Hopper paintings such every bit Early Sunday Morning (1930), Summertime (1943), Vii A.M. (1948), and Sun in an Empty Room (1963). His use of low-cal and shadow furnishings have been compared to the cinematography of film noir.[73]

Although a realist painter, Hopper's "soft" realism simplified shapes and details. He used saturated color to heighten contrast and create mood.

Subjects and themes [edit]

Hopper derived his subject matter from ii principal sources: 1, the common features of American life (gas stations, motels, restaurants, theaters, railroads, and street scenes) and its inhabitants; and two, seascapes and rural landscapes. Regarding his style, Hopper defined himself every bit "an constructing of many races" and non a member of any schoolhouse, particularly the "Ashcan School".[74] Once Hopper accomplished his mature style, his art remained consistent and self-contained, in spite of the numerous art trends that came and went during his long career.[74]

Hopper'southward seascapes fall into three main groups: pure landscapes of rocks, bounding main, and beach grass; lighthouses and farmhouses; and sailboats. Sometimes he combined these elements. Well-nigh of these paintings depict strong low-cal and fair weather; he showed little interest in snow or rain scenes, or in seasonal color changes. He painted the majority of the pure seascapes in the period betwixt 1916 and 1919 on Monhegan Island.[75] Hopper's The Long Leg (1935) is a nearly all-blueish sailing movie with the simplest of elements, while his Footing Swell (1939) is more complex and depicts a group of youngsters out for a canvass, a theme reminiscent of Winslow Homer's iconic Breezing Up (1876).[76]

Urban architecture and cityscapes also were major subjects for Hopper. He was fascinated with the American urban scene, "our native architecture with its hideous beauty, its fantastic roofs, pseudo-gothic, French Mansard, Colonial, mongrel or what non, with centre-searing color or delicate harmonies of faded paint, shouldering ane some other along interminable streets that taper off into swamps or dump heaps."[77]

In 1925, he produced Business firm by the Railroad. This classic work depicts an isolated Victorian forest mansion, partly obscured by the raised embankment of a railroad. It marked Hopper's creative maturity. Lloyd Goodrich praised the work as "one of the most poignant and desolating pieces of realism."[78] The work is the first of a series of stark rural and urban scenes that uses sharp lines and large shapes, played upon by unusual lighting to capture the lonely mood of his subjects. Although critics and viewers translate pregnant and mood in these cityscapes, Hopper insisted "I was more interested in the sunlight on the buildings and on the figures than any symbolism."[79] As if to prove the bespeak, his belatedly painting Sunday in an Empty Room (1963) is a pure study of sunlight.[eighty]

Well-nigh of Hopper'south figure paintings focus on the subtle interaction of human being beings with their environment—carried out with solo figures, couples, or groups. His principal emotional themes are solitude, loneliness, regret, boredom, and resignation. He expresses the emotions in various environments, including the office, in public places, in apartments, on the road, or on vacation.[81] Every bit if he were creating stills for a movie or tableaux in a play, Hopper positioned his characters as if they were captured just before or just after the climax of a scene.[82]

Hopper's solitary figures are mostly women—dressed, semi-clad, and nude—often reading or looking out a window, or in the workplace. In the early 1920s, Hopper painted his first such images Girl at Sewing Car (1921), New York Interior (some other adult female sewing) (1921), and Moonlight Interior (a nude getting into bed) (1923). Automat (1927) and Hotel Room (1931), all the same, are more representative of his mature style, emphasizing the confinement more overtly.[83]

Every bit Hopper scholar, Gail Levin, wrote of Hotel Room:

The spare vertical and diagonal bands of color and sharp electric shadows create a concise and intense drama in the night...Combining poignant field of study matter with such a powerful formal arrangement, Hopper'south limerick is pure plenty to approach an almost abstruse sensibility, yet layered with a poetic meaning for the observer.[84]

Hopper's Room in New York (1932) and Cape Cod Evening (1939) are prime examples of his "couple" paintings. In the first, a young couple appear alienated and uncommunicative—he reading the newspaper while she idles by the pianoforte. The viewer takes on the role of a voyeur, every bit if looking with a telescope through the window of the apartment to spy on the couple's lack of intimacy. In the latter painting, an older couple with picayune to say to each other, are playing with their canis familiaris, whose own attention is fatigued away from his masters.[85] Hopper takes the couple theme to a more than ambitious level with Circuit into Philosophy (1959). A center-aged man sits dejectedly on the edge of a bed. Beside him lies an open book and a partially clad woman. A shaft of light illuminates the floor in front of him. Jo Hopper noted in their log book, "[T]he open volume is Plato, reread besides late".

Levin interprets the painting:

Plato's philosopher, in search of the real and the true, must turn away from this transitory realm and contemplate the eternal Forms and Ideas. The pensive human being in Hopper'southward painting is positioned betwixt the lure of the earthly domain, figured by the adult female, and the call of the higher spiritual domain, represented past the ethereal lightfall. The pain of thinking nigh this choice and its consequences, later on reading Plato all night, is evident. He is paralysed past the fervent inner labour of the melancholic.[86]

In Office at Nighttime (1940), some other "couple" painting, Hopper creates a psychological puzzle. The painting shows a man focusing on his piece of work papers, while nearby his attractive female secretary pulls a file. Several studies for the painting show how Hopper experimented with the positioning of the ii figures, perhaps to heighten the eroticism and the tension. Hopper presents the viewer with the possibilities that the homo is either truly uninterested in the adult female'due south appeal or that he is working hard to ignore her. Another interesting aspect of the painting is how Hopper employs three light sources,[85] from a desk lamp, through a window and indirect light from higher up. Hopper went on to make several "role" pictures, only no others with a sensual undercurrent.

The all-time known of Hopper's paintings, Nighthawks (1942), is one of his paintings of groups. Information technology shows customers sitting at the counter of an all-night diner. The shapes and diagonals are carefully constructed. The viewpoint is cinematic—from the sidewalk, every bit if the viewer were budgeted the restaurant. The diner's harsh electric light sets information technology apart from the dark night exterior, enhancing the mood and subtle emotion.[87] As in many Hopper paintings, the interaction is minimal. The eatery depicted was inspired by i in Greenwich Village. Both Hopper and his wife posed for the figures, and Jo Hopper gave the painting its title. The inspiration for the picture may accept come up from Ernest Hemingway's short story "The Killers", which Hopper greatly admired,[88] or from the more than philosophical "A Make clean, Well-Lighted Place".[89] The mood of the painting has sometimes been interpreted equally an expression of wartime anxiety.[90] In keeping with the title of his painting, Hopper later said, Nighthawks has more than to do with the possibility of predators in the nighttime than with loneliness.[91]

His second nearly recognizable painting afterwards Nighthawks is another urban painting, Early Sunday Forenoon (originally called Seventh Artery Shops), which shows an empty street scene in sharp side light, with a fire hydrant and a barber pole as stand up-ins for man figures. Originally Hopper intended to put figures in the upstairs windows but left them empty to heighten the feeling of desolation.[92]

Hopper'due south rural New England scenes, such as Gas (1940), are no less meaningful. Gas represents "a different, equally clean, well-lighted refuge ... ke[pt] open for those in demand as they navigate the nighttime, traveling their own miles to go before they sleep."[93] The work presents a fusion of several Hopper themes: the alone effigy, the melancholy of dusk, and the lone route.[94]

Hopper approaches Surrealism with Rooms by the Ocean (1951), where an open door gives a view of the ocean, without an apparent ladder or steps and no indication of a beach.[95]

After his student years, Hopper's nudes were all women. Dissimilar past artists who painted the female nude to glorify the female person form and to highlight female eroticism, Hopper's nudes are solitary women who are psychologically exposed.[96] One audacious exception is Girlie Show (1941), where a cherry-red-headed strip-tease queen strides confidently across a stage to the accessory of the musicians in the pit. Girlie Show was inspired past Hopper'southward visit to a caricatural show a few days earlier. Hopper'due south wife, as usual, posed for him for the painting, and noted in her diary, "Ed beginning a new canvas—a burlesque queen doing a strip tease—and I posing without a stitch on in forepart of the stove—nix only high heels in a lottery trip the light fantastic pose."[97]

Hopper's portraits and cocky-portraits were relatively few after his student years.[98] Hopper did produce a commissioned "portrait" of a firm, The MacArthurs' Home (1939), where he faithfully details the Victorian architecture of the home of actress Helen Hayes. She reported later, "I gauge I never met a more misanthropic, grumpy individual in my life." Hopper grumbled throughout the project and never once again accustomed a commission.[99] Hopper too painted Portrait of Orleans (1950), a "portrait" of the Greatcoat Cod town from its chief street.[100]

Though very interested in the American Civil War and Mathew Brady's battlefield photographs, Hopper fabricated only two historical paintings. Both depicted soldiers on their way to Gettysburg.[101] Also rare among his themes are paintings showing action. The all-time instance of an activeness painting is Bridle Path (1939), but Hopper's struggle with the proper anatomy of the horses may accept discouraged him from similar attempts.[102]

Hopper'southward concluding oil painting, Ii Comedians (1966), painted one year before his decease, focuses on his love of the theater. Two French pantomime actors, one male and one female person, both dressed in bright white costumes, take their bow in front of a darkened stage. Jo Hopper confirmed that her husband intended the figures to suggest their taking their life's last bows together as husband and wife.[103]

Hopper'southward paintings have ofttimes been seen by others as having a narrative or thematic content that the artist may non have intended. Much significant can be added to a painting by its title, but the titles of Hopper'south paintings were sometimes chosen by others, or were selected past Hopper and his wife in a way that makes it unclear whether they have whatever real connection with the artist's meaning. For instance, Hopper once told an interviewer that he was "fond of Early Sunday Morning... only information technology wasn't necessarily Lord's day. That word was tacked on subsequently past someone else."[104]

The tendency to read thematic or narrative content into Hopper'southward paintings, that Hopper had non intended, extended even to his wife. When Jo Hopper commented on the figure in Cape Cod Morning "It's a woman looking out to see if the weather's adept enough to hang out her launder," Hopper retorted, "Did I say that? You're making it Norman Rockwell. From my point of view she's merely looking out the window."[105] Another example of the same phenomenon is recorded in a 1948 article in Time:

Hopper'due south Summer Evening, a immature couple talking in the harsh light of a cottage porch, is inescapably romantic, but Hopper was hurt by one critic's proposition that it would do for an illustration in "whatsoever adult female's magazine." Hopper had the painting in the back of his caput "for 20 years and I never thought of putting the figures in until I actually started last summer. Why any fine art manager would tear the picture apart. The figures were non what interested me; it was the calorie-free streaming down, and the dark all around."[106]

Identify in American art [edit]

New York Eating house (1922)

In focusing primarily on quiet moments, very rarely showing action, Hopper employed a form of realism adopted by another leading American realist, Andrew Wyeth, but Hopper'due south technique was completely unlike from Wyeth's hyper-detailed manner.[l] In league with some of his contemporaries, Hopper shared his urban sensibility with John Sloan and George Bellows, but avoided their overt action and violence. Where Joseph Stella and Georgia O'Keeffe glamorized the awe-inspiring structures of the metropolis, Hopper reduced them to everyday geometrics and he depicted the pulse of the city as desolate and unsafe rather than "elegant or seductive".[107]

Charles Burchfield, whom Hopper admired and to whom he was compared, said of Hopper, "he achieves such a complete verity that you tin read into his interpretations of houses and conceptions of New York life whatever human implications you lot wish."[108] He also attributed Hopper's success to his "bold individualism. ... In him we have regained that sturdy American independence which Thomas Eakins gave us, but which for a time was lost."[109] Hopper considered this a high compliment since he considered Eakins the greatest American painter.[110]

Hopper scholar Deborah Lyons writes, "Our own moments of revelation are often mirrored, transcendent, in his work. Once seen, Hopper'due south interpretations exist in our consciousness in tandem with our own experience. We forever see a certain type of house as a Hopper business firm, invested perhaps with a mystery that Hopper implanted in our own vision." Hopper's paintings highlight the seemingly mundane and typical scenes in our everyday life and requite them crusade for epiphany. In this fashion Hopper's art takes the gritty American landscape and lonely gas stations and creates within them a sense of beautiful anticipation.[111]

Although compared to his contemporary Norman Rockwell in terms of discipline matter, Hopper did not like the comparison. Hopper considered himself more subtle, less illustrative, and certainly not sentimental. Hopper also rejected comparisons with Grant Woods and Thomas Hart Benton stating "I recollect the American Scene painters caricatured America. I ever wanted to do myself."[112]

Influence [edit]

Hopper'southward influence on the art world and pop culture is undeniable; see § In pop civilisation for numerous examples. Though he had no formal students, many artists take cited him as an influence, including Willem de Kooning, Jim Dine, and Mark Rothko.[74] An illustration of Hopper's influence is Rothko'due south early piece of work Limerick I (c. 1931), which is a direct paraphrase of Hopper's Chop Suey.[113]

Hopper's cinematic compositions and dramatic utilize of lite and dark take made him a favorite among filmmakers. For example, House by the Railroad is reported to have heavily influenced the iconic house in the Alfred Hitchcock film Psycho.[114] The same painting has besides been cited as being an influence on the dwelling house in the Terrence Malick motion picture Days of Heaven. The 1981 motion-picture show Pennies from Heaven includes a tableau vivant of Nighthawks, with the lead actors in the places of the diners. German manager Wim Wenders also cites Hopper influence.[74] His 1997 picture The End of Violence besides incorporates a tableau vivant of Nighthawks, recreated past actors. Noted surrealist horror flick director Dario Argento went so far every bit to recreate the diner and the patrons in Nighthawks as role of a set for his 1976 film Deep Red (aka Profondo Rosso). Ridley Scott has cited the same painting equally a visual inspiration for Blade Runner. To institute the lighting of scenes in the 2002 motion-picture show Road to Perdition, director Sam Mendes drew from the paintings of Hopper as a source of inspiration, particularly New York Motion picture.[115]

Homages to Nighthawks featuring cartoon characters or famous pop culture icons such as James Dean and Marilyn Monroe are often found in poster stores and souvenir shops. The cable telly channel Turner Archetype Movies sometimes runs animated clips based on Hopper paintings prior to airing its films. Musical influences include singer/songwriter Tom Waits's 1975 alive-in-the-studio album titled Nighthawks at the Diner, after the painting. In 1993, Madonna was inspired sufficiently by Hopper'due south 1941 painting Girlie Show that she named her globe tour after it and incorporated many of the theatrical elements and mood of the painting into the show. In 2004, British guitarist John Squire (formerly of The Stone Roses) released a concept anthology based on Hopper's work entitled Marshall'south House. Each song on the album is inspired by, and shares its championship with, a painting by Hopper. Canadian rock group The Weakerthans released their anthology Reunion Bout in 2007 featuring two songs inspired by and named later on Hopper paintings, "Sun in an Empty Room", and "Night Windows", and have likewise referenced him in songs such equally "Infirmary Vespers". Hopper'due south Compartment C, Automobile 293 inspired Polish composer Paweł Szymański's Compartment 2, Car vii for violin, viola, cello and vibraphone (2003), every bit well as Hubert-Félix Thiéfaine's song Compartiment C Voiture 293 Edward Hopper 1938 (2011). Hopper's work has influenced multiple recordings past British ring Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark. Early Sunday Morning was the inspiration for the sleeve of Crush (1985). The aforementioned band's 2013 single "Night Café" was influenced by Nighthawks and mentions Hopper past proper name. Seven of his paintings are referenced in the lyrics.[116]

In verse, numerous poems take been inspired by Hopper's paintings, typically as vivid descriptions and dramatizations; this genre is known as ekphrasis. In addition to numerous individual poems inspired past Hopper, several poets have written collections based on Hopper's paintings. The French poet Claude Esteban wrote a drove of prose poems, Soleil dans une pièce vide (Sun in an Empty room, 1991), based on twoscore-seven Hopper paintings from betwixt 1921 and 1963, ending with Sun in an Empty room (1963), hence the title.[117] The poems each dramatized a Hopper painting, imagining a story behind the scene; the book won the Prix French republic Civilisation prize in 1991. Eight of the poems – Footing Swell, Girl at Sewing Machine, Compartment C, Car 293, Nighthawks, S Carolina Morning, House by the Railroad, People in the Dominicus, and Roofs of Washington Foursquare – were subsequently set to music past composer Graciane Finzi, and recorded with reading by the singer Natalie Dessay on her anthology Portraits of America (2016), where they were supplemented by selecting 10 additional Hopper paintings, and songs from the American songbook to go with them.[118] Similarly, the Castilian poet Ernest Farrés wrote a collection of 50-one poems in Catalan, under the name Edward Hopper (2006, English translation 2010 by Lawrence Venuti), and James Hoggard wrote Triangles of Light: The Edward Hopper Poems (Wings Press, 2009). A drove by diverse poets was organized in The Poetry of Solitude: A Tribute to Edward Hopper 1995 (editor Gail Levin). Individual poems include Byron Vazakas (1957) and John Stone (1985) inspired by Early Sunday Morning time, and Mary Leader inspired by Girl at Sewing Motorcar.

Exhibitions [edit]

In 1980, the show Edward Hopper: The Fine art and the Artist opened at the Whitney Museum of American Art and visited London, Düsseldorf, and Amsterdam, also equally San Francisco and Chicago. For the first time ever, this show presented Hopper'southward oil paintings together with preparatory studies for those works. This was the beginning of Hopper's popularity in Europe and his large worldwide reputation.[ citation needed ]

In 2004, a large selection of Hopper's paintings toured Europe, visiting Museum Ludwig in Cologne, Germany, and the Tate Modern in London. The Tate exhibition became the second most popular in the gallery's history, with 420,000 visitors in the iii months it was open.

In 2007, an exhibition focused on the period of Hopper's greatest achievements—from almost 1925 to mid-century—and was presented at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The exhibit comprised fifty oil paintings, xxx watercolors, and twelve prints, including the favorites Nighthawks, Chop Suey, and Lighthouse and Buildings. The exhibition was organized by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the National Gallery of Fine art, Washington, and the Art Institute of Chicago and sponsored by the global management consulting firm Booz Allen Hamilton.

In 2010, the Fondation de 50'Hermitage museum in Lausanne, Switzerland, held an exhibition that covered Hopper's unabridged career, with works drawn largely from the Whitney Museum in New York City. It included paintings, watercolors, etchings, cartoons, posters, every bit well as some of the preparatory studies for selected paintings. The exhibition had previously been seen in Milan and Rome. In 2011, The Whitney Museum of American Art held an exhibition called Edward Hopper and His Times.

In 2012, an exhibition opened at the Grand Palais in Paris that sought to shed light on the complexity of his masterpieces, which is an indication of the richness of Hopper's oeuvre. Information technology was divided chronologically into two main parts: the first department covered Hopper'southward formative years (1900–1924), comparing his work with that of his contemporaries and art he saw in Paris, which may have influenced him. The second section looked at the fine art of his mature years, from the showtime paintings allegorical of his personal style, such as House by the Railroad (1924), to his final works.

In 2020, Fondation Beyeler held an exhibition displaying Hopper'due south art. The exhibition focused on Hopper's "iconic representations of the infinite expanse of American landscapes and cityscapes".[119] This aspect has rarely been referred to in exhibitions, nonetheless it is a central ingredient to understanding Hopper's piece of work.

Art market [edit]

Works by Hopper rarely appear on the market. The creative person was non prolific, painting just 366 canvases; during the 1950s, when he was in his 70s, he produced approximately five paintings a yr. Hopper's longtime dealer, Frank Rehn, who gave the artist his get-go solo testify in 1924, sold Hotel Window (1956) to collector Olga Knoepke for $vii,000 (equivalent to $64,501 in 2020) in 1957. In 1999, the Forbes Collection sold it to histrion Steve Martin privately for around $x million.[120] In 2006, Martin sold it for $26.89 meg at Sotheby'south New York, an auction record for the artist.[121]

In 2013 the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts put Hopper's Due east Wind Over Weehawken (1934) up for sale, hoping to garner the $22–$28 million at which the painting is valued,[122] in order to found a fund to acquire "contemporary art" that would appreciate in value.[123] It is a street scene rendered in dark, earthy tones depicting the gabled firm at 1001 Boulevard E at the corner of 49th Street in Weehawken, New Jersey, and is considered one of Hopper's all-time works.[124] Information technology was acquired directly from the dealer handling the artist's paintings in 1952, fifteen years before the death of the painter, at a very low toll. The painting sold for a record-breaking $36 1000000 at Christie's in New York,[123] to an anonymous phone applicant.

In 2018, later the decease of art collector Barney A. Ebsworth and subsequent auction of many of the pieces from his collection, Chop Suey (1929) was sold for $92 one thousand thousand, condign the virtually expensive of Hopper's work ever bought at auction.[125] [126]

In pop culture [edit]

In addition to his influence (run into § Influence), Hopper is frequently referenced in pop civilisation.

In 1981, Hopper's Silence, a documentary by Brian O'Doherty produced past the Whitney Museum of American Art, was shown at the New York Film Festival at Alice Tully Hall.[127]

Austrian director Gustav Deutsch created the 2013 motion-picture show Shirley – Visions of Reality based on thirteen of Edward Hopper'southward paintings.[128] [129]

Other works based on or inspired by Hopper's paintings include Tom Waits's 1975 album Nighthawks at the Diner, and a 2012 series of photographs by Gail Albert Halaban.[129] [130]

In the volume (1985, 1998) and traveling exhibition chosen Hopper'due south Places, Gail Levin located and photographed the sites for many of Hopper's paintings. In her 1985 review of a related bear witness organized past Levin, Vivien Raynor wrote in the New York Times: "Miss Levin'due south deductions are invariably enlightening, as when she infers that Hopper's tendency to elongate structures was a reflection of his ain bully height."[131]

New wave band Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Nighttime'south 1985 album Crush features artwork inspired past several Hopper paintings, including Early Sunday Forenoon, Nighthawks and Room in New York.[132] The band'due south 2013 single "Night Cafe" was influenced by Nighthawks and mentions Hopper past name. Seven of his paintings are referenced in the lyrics.[116]

The New York City Opera staged the E Coast premiere of Stewart Wallace's "Hopper's Wife" – a 1997 chamber opera most an imagined marriage between Edward Hopper and the gossip columnist Hedda Hopper, at Harlem Stage in 2016.[133]

Irish novelist, Christine Dwyer Hickey, published a novel, The Narrow Land, in 2022 in which Edward and Jo Hopper were fundamental characters.[134]

Paul Weller included a song named 'Hopper' on his 2022 album A Kind Revolution.

Selected works [edit]

| Title | Medium | Appointment | Collection | Dimensions | Prototype |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daughter at Sewing Motorcar | oil on sheet | 1921 | Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum | 48 cm × 46 cm (nineteen in × 18 in) |  |

| Business firm by the Railroad | oil on canvas | 1925 | Museum of Modern Fine art | 61 cm. x 73,7 cm. |  |

| Automat | oil on canvass | 1927 | Des Moines Art Center | 71.4 cm × 91.four cm (28 in × 36 in) |  |

| Manhattan Bridge Loop | oil on canvas | 1928 | Addison Gallery of American Fine art | 88,9x152,4cm.(35x60in) |  |

| Chop Suey | oil on canvas | 1929 | Barney A. Ebsworth Collection | 81.three cm × 96.5 cm (32 in × 38 in) |  |

| Early on Sun Morning | oil on canvass | 1930 | Whitney Museum of American Art | 89.iv cm × 153 cm (35.2 in × threescore.three in) |  |

| Office at Nighttime | oil on canvas | 1940 | Walker Art Centre (Minneapolis) | 56.356 cm × 63.82 cm (22.1875 in × 25.125 in) |  |

| Nighthawks | oil on canvas | 1942 | Art Institute of Chicago | 84.ane cm × 152.4 cm (33 one⁄8 in × 60 in) |  |

| Hotel Antechamber | oil on sail | 1943 | Indianapolis Museum of Art | 81.9 cm × 103.5 cm (32 1⁄4 in × forty 3⁄4 in) | |

| Role in a Small City | oil on canvas | 1953 | Metropolitan Museum of Art | 71 cm × 102 cm (28 in × forty in) |

Notes [edit]

- ^ Levin, Gail (1999). "Hopper, Edward". American National Biography. New York: Oxford Academy Press. (subscription required)

- ^ "Edward Hopper (1882–1967)". metmuseum.org.

- ^ a b Levin, Gail, Edward Hopper: An Intimate Biography, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1995, p.eleven, ISBN 0-394-54664-4

- ^ Levin 1995, p. 9

- ^ Levin 1995, p. 12

- ^ Levin 1995, p. 23

- ^ "Edward Hopper House Fine art Center – Edward Hopper House".

- ^ "National Register Information Arrangement". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- ^ Levin 1995, p. 12, 16

- ^ a b Levin 1995, p. 16-eighteen

- ^ Levin 1995, p. 20

- ^ Shadwick, Louis, "The Origins of Edward Hopper'southward Earliest Oil Paintings", The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 162 (October 2020) pp.870-877

- ^ Gopnik, Blake (October two, 2020). "Early Works by Edward Hopper Found to Be Copies of Other Artists". The New York Times.

- ^ Levin 1995, p. 23, 25

- ^ Brenner, Elsa (December 5, 2004). "A Trio of Villages Hugging the Hudson". The New York Times . Retrieved May 4, 2008.

- ^ a b c Maker 1990, p. 8

- ^ Wagstaff, Sheena Ed., Edward Hopper, Tate Publishing, London, 2004, p. 16, ISBN 1-85437-533-four

- ^ Levin 1995, p. twoscore

- ^ a b Maker 1990, p. 9

- ^ Levin 2001, p. 19

- ^ Levin 2001, p. 38

- ^ Levin 1995, p. 48

- ^ Maker 1990, p. 11

- ^ Wagstaff 2004, p. 17

- ^ Levin 1995, p. 66

- ^ Maker 1990, p. 10

- ^ Levin 1995, p. 85

- ^ a b c Levin 1995, p. 88

- ^ Wagstaff 2004, p. 53

- ^ Levin 2001, p. 88

- ^ Levin 2001, p. 107

- ^ Levin 1995, p. 90

- ^ Gail Levin. Hopper, Edward, American National Biography Online, February 2000. Retrieved December twenty, 2015.

- ^ Wagstaff 2004, p. 227

- ^ Levin 2001, pp. 74–77

- ^ Maker 1990, p. 12

- ^ Kranzfelder, Ivo, and Edward Hopper, Edward Hopper, 1882–1967: Vision of Reality, New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 2003, p. thirteen, ISBN 0760748772

- ^ a b Levin 1995, p. 120

- ^ Levin 1980, pp. 29–33

- ^ Maker 1990, p. 13-15

- ^ Levin 2001, p. 151, 153

- ^ Levin 2001, pp. 152, 155

- ^ Levin, Gail, "Edward Hopper: Chronology" in Edward Hopper at Kennedy Galleries New York: Kennedy Galleries, 1977.

- ^ a b c Maker 1990, p. 16

- ^ a b Levin 1995, p. 171

- ^ Hopper'southward Gloucester, Andrea Shea, WBUR, July 6, 2007.

- ^ a b c Wagstaff 2004, p. 230

- ^ Levin 2001, p. 161

- ^ Levin 2001, p. 246

- ^ a b c Maker 1990, p. 17

- ^ Allman, William One thousand. (Feb 10, 2014). "New additions to the Oval Office". whitehouse.gov . Retrieved February 11, 2016 – via National Archives.

- ^ Clause 2012

- ^ a b Wagstaff 2004, p. 232

- ^ Wagstaff 2004, p. 233

- ^ (de) Grave of Edward Hopper at knerger.de

- ^ Wagstaff 2004, p. 235

- ^ Anfam, David, "Review of 'A Catalogue of Raisonne by -Gail Levin'," The Burlington Magazine, 1999.

- ^ Strand, Mark, Hopper, Knopf Publishing, 1994 ISBN 9780307701244

- ^ Berman, Avis, "Hopper the Supreme American Realist of the 20th Century", Smithsonian Magazine June 2007

- ^ Strand, Mark, "Review of 'Hopper Drawing' Whitney Museum 2013", The New York Review of Books, June 2015

- ^ Art Digest April 1937 'Carnegie Traces Hopper's Ascent to Fame'

- ^ "The Silent Witness", Time, December 24, 1956

- ^ Maker, Sherry, Edward Hopper, Brompton Books, New York, 1990, p. 6, ISBN 0-517-01518-eight

- ^ Goodrich, Lloyd, "The Paintings of Edward Hopper", The Arts, March 1927

- ^ Interview in 1960 with Katherine Kuhn, quoted in her The Creative person'southward Voice, Harper and Row, New York, 1960

- ^ Wagstaff 2004, p. 88

- ^ Wagstaff 2004, pp. 84–86

- ^ Edward Hopper, "Argument." Published equally a function of "Statements past 4 Artists" in Reality, vol. 1, no. 1 (bound 1953). Hopper's handwritten draft is reproduced in Levin, Edward Hopper: An Intimate Biography, p. 461.

- ^ Wagstaff 2004, p. 71

- ^ Wagstaff 2004, p. 98

- ^ Levin 2001, p. 254

- ^ Levin 2001, p. 261

- ^ Wagstaff 2004, p. 92

- ^ a b c d Wagstaff 2004, p. thirteen

- ^ Levin 2001, pp. 130–145

- ^ Levin 2001, p. 266

- ^ Wagstaff 2004, p. 67

- ^ Wagstaff 2004, p. 229

- ^ Wagstaff 2004, p. 12

- ^ Wagstaff 2004, p. 28

- ^ Wagstaff 2004, pp. 70–71

- ^ Goodrich, Lloyd, Edward Hopper, New York Urban center: H. North. Abrams, 1971

- ^ Levin 2001, p. 169, 213

- ^ Levin 2001, p. 212

- ^ a b Levin 2001, p. 220, 264

- ^ Wagstaff 2004, p. 55

- ^ Levin 2001, p. 288

- ^ Hopper wrote: "I want to compliment you for printing Ernest Hemingway's "The Killers" in the March Scribner's. It is refreshing to come upon such a honest piece of work in an American magazine, after wading through the vast sea of sugar coated mush that makes up the most of our fiction. Of the concessions to popular prejudices, the side stepping of truth, and the ingenious mechanism of the trick ending there is no taint in this story.", Edward Hopper to the editor, Scribner's Magazine, 82 (June 1927), p. 706d, quoted in Levin (1979, p. vii) harvtxt mistake: no target: CITEREFLevin1979 (assistance), Levin (1979, note 25) harvtxt error: no target: CITEREFLevin1979 (help)

- ^ Wagstaff 2004, p. 44

- ^ Jessica Murphy (June 2007). "Edward Hopper (1882–1967)". www.metmuseum.org . Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- ^ Levin 1995, p. 350

- ^ Levin 2001, p. 198

- ^ Wells, Walter (2007). Silent Theater: The Fine art of Edward Hopper. London/New York: Phaidon Press. ISBN978-0714845418.

- ^ Levin 2001, p. 278

- ^ Maker 1990, p. 37

- ^ Wagstaff 2004, p. 20

- ^ Levin 2001, p. 282

- ^ Levin 2001, p. 162

- ^ Levin 2001, p. 268

- ^ Levin 2001, p. 332

- ^ Levin 2001, p. 274

- ^ Levin 2001, p. 262

- ^ Levin 2001, p. 380

- ^ Interview with Hopper in Katharine Kuh, The Artist's Voice: Talks with Seventeen Modernistic Artists. Originally published 1962. New York: Da Capo, 2000, p. 134.

- ^ Levin 2001, p. 334

- ^ "Travelling Human being", Fourth dimension, January 19, 1948, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Maker 1990, p. 43

- ^ Maker 1990, p. 65

- ^ Wagstaff 2004, p. fifteen

- ^ Wagstaff 2004, p. 23

- ^ Deborah Lyons, Edward Hopper and The American Imagination, New York, 1995, p. XII, ISBN 0-393-31329-eight

- ^ Maker 1990, p. nineteen

- ^ Wagstaff 2004, p. 36

- ^ Wagstaff 2004, p. 234

- ^ Ray Zone. "A Master of Mood". American Cinematographer. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- ^ a b "Premiere: OMD, 'Night Café' (Vile Electrodes 'B-Side the C-Side' Remix)". Slicing Up Eyeballs. Baronial 5, 2013. Retrieved September 25, 2013.

- ^ Sample poem: Trois fenêtres, la nuit (Night windows), notes

- ^ Pictures of America, November 24, 2016, archived from the original on February ii, 2017

- ^ N/A, FONDATION BEYELER (2020). "Edward Hopper". FONDATION BEYELER . Retrieved January three, 2021.

- ^ Vogel, Carol. (Oct vi, 2006). Edward Hopper Paintings Modify at Whitney Bear witness The New York Times.

- ^ Linsay Pollock (Nov 29, 2006). "Steve Martin Hopper, Wistful Rockwell Pause Auction Records". Bloomberg.

- ^ Salisbury, Stephan (Baronial 29, 2013). "Pennsylvania Academy to sell Hopper painting". philly.com.

- ^ a b Carswell, Vonecia (December half-dozen, 2013). "1934 'E Wind Over Weehawken' painting sells for $36M at Christie's sale". The Jersey Journal.

- ^ Schwartz, Fine art (December 29, 2013). "Hopper comes habitation Woman buys mod version of $40M painting depicting her house on Boulevard E". Hudson Reporter. Archived from the original on April 9, 2016. Retrieved January 7, 2013.

- ^ "Hopper'southward Chop Suey in record-breaking $92m auction". BBC News. Nov 14, 2018. Retrieved Nov 14, 2018.

- ^ Scott Reyburn (Nov thirteen, 2018). "Hopper Painting Sells for Record $91.9 Million at Christie's". The New York Times . Retrieved November 13, 2018.

- ^ Lor. (October 21, 1981). "Film Reviews: Hopper's Silence". Variety.

- ^ Gustav Deutsch brings Hopper'southward paintings alive. Retrieved on April viii, 2014

- ^ a b "Edward Hopper comes to the silver screen". Phaidon Press. Feb 2013. Retrieved August 2, 2014.

- ^ Bosman, Julie (July 20, 2012). "The Original Hoppers". The New York Times . Retrieved August 2, 2014.

- ^ Raynor, Vivian (October xx, 1985). "Art:The Unusual, The Instructive And The Mysterious At Rutgers". The New York Times . Retrieved June iii, 2014.

- ^ "Archetype anthology covers:Shell–OMD". Never Mind the Bus Pass. Archived from the original on July 4, 2017. Retrieved May 28, 2017.

- ^ Martin Bernheimer, Hopper's Wife, New York City Opera, New York-'Ramblings and Rumblings', Financial Times, 2 May 2016. Retrieved xvi March 2019

- ^ Christine Dwyer Hickey, I Lost a Kidney and Gained a Novel, Irish Times, 9 March 2019

References [edit]

- Clause, Bonnie Tocher.Edward Hopper in Vermont, (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England, 2012)

- Goodrich, Lloyd. Edward Hopper, (New York: H. N. Abrams, 1971)

- Haskell, Barbara. Modernistic Life: Edward Hopper and His Time, (Hamburg: Bucerius Kunst Forum, 2009)

- Healy, Pat. "Look at all the alone people: MFA's 'Hopper' celebrates solitude", Metro newspaper, Tuesday, May 8, 2007, p. 18.

- Kranzfelder, Ivo. Hopper (New York: Taschen, 1994)

- Kuh, Katharine. Interview with Edward Hopper in Katherine Kuh, The Artist'southward Voice: Talks with Seventeen Artists. (New York: 1962, Di Capo Press, 2000, pp. 130–142)

- Levin, Gail. Edward Hopper (New York: Crown, 1984)

- Levin, Gail. Edward Hopper: A Catalogue Raisonne (New York: Norton, 1995)

- Levin, Gail. Edward Hopper: An Intimate Biography (New York: Knopf, 1995; Rizzoli Books, 2007)

- Levin, Gail. Edward Hopper: Gli anni della formazione (Milan: Electra Editrice, 1981)

- Levin, Gail. Edward Hopper: The Art and the Creative person (New York: Norton, 1980, London, 1981; Munich: Schirmer/Mosel, 1986)

- Levin, Gail. Edward Hopper: The Complete Prints (New York: Norton, 1979, London, 1980; Munich: Schirmer/Mosel, 1986)

- Levin, Gail. Edward Hopper as Illustrator (New York: Norton, 1979, London, 1980) (archive)

- Levin, Gail. Hopper's Places (New York: Knopf, 1985; 2nd expanded edition, University of California Press, 1998)

- Levin, Gail. The Complete Oil Paintings of Edward Hopper (New York: Norton, 2001)

- Lyons, Deborah, Brian O'Doherty. Edward Hopper: A Periodical of His Piece of work (New York: Norton, 1997)

- Maker, Sherry. Edward Hopper (New York: Brompton Books, 1990)

- Mecklenburg, Virginia M. Edward Hopper: The Watercolors (New York: Norton, 1999)

- Renner, Rolf G. Edward Hopper 1882–1967: Transformation of the Real (New York: Taschen, 1999)

- Wagstaff, Sheena, Ed. Edward Hopper (London, Tate Publishing, London)

- Wells, Walter. Silent Theater: The Art of Edward Hopper (London/New York: Phaidon, 2007). Winner of the 2009 Umhoefer Prize for Accomplishment in the Arts and Humanities.

- Hopper, Edward (1931). Edward Hopper. New York: Whitney Museum of American Fine art.

- Pabón, Gutierrez, Fernández, Martinez-Pietro (2013). "Linked Open Data technologies for publication of census microdata". Journal of the American Order for Information science and Technology. 64 (9): 1802–1814. doi:x.1002/asi.22876. hdl:10533/127539.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Tziomis, Leatha (2012). Botticelli´s La Primavera: Painting the cosmos of human ideals.

- Kalin, Ian (2014). "Open Data improves Democracy". SAIS Review of International Affairs. 34 (1): 59–lxx. doi:10.1353/sais.2014.0006. S2CID 154068669.

External links [edit]

- Edward Hopper at the National Gallery of Fine art, Washington

- An Edward Hopper Scrapbook compiled by the staff of the Smithsonian

- Oral history interview with Edward Hopper, June 17, 1959 from the Smithsonian Archives of American Art

- Exhaustive list of Hopper'due south works (in High german)

- Gallery of Edward Hopper'due south Paintings

- Smithsonian Archives of American Art: Edward Hopper letter of the alphabet to Agnes Albert (1955)

- "Edward Hopper all around Gloucester, MA" — 100+ paintings, drawings, and prints, with images then and now.

- explore Google Maps: Locations of "Edward Hopper all effectually Gloucester" sites

- Gloucester MA HarborWalk Edward Hopper Story Moment, with additional links, one stop forth free public access walkway.

- Biblioklept.org: Notes on Painting 1933

- Edward Hopper House Art Eye website — not-profit art heart for contemporary art exhibitions at birthplace/childhood home in Nyack

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Hopper

0 Response to "Id Painting/lonely Old Woman in Front of Stove Reading"

Post a Comment